Book: Keopuolani, Sacred Wife, Queen Mother, 1778-1823 by Esther T. Mookini

ESTHER T. MOOKINI

Keopuolani, Sacred Wife, Queen Mother, 1778-1823

KEOPUOLANI, DAUGHTER OF KINGS, wife of a king, and mother of two kings, was the last direct descendant of the ancient kings of Hawai'i and Maui and the last of the female ali'i (chief) whose mana was equal to that of the gods. From May 1819 to March 1820 she was the central figure in the kingdom's history. Her husband, Kamehameha, had already united the islands under his rule. On May 8 or 14, 1819, he died in Kailua, Kona. It was during the mourning period that the ancient kapu system collapsed, and Keopuolani was instrumental in this dramatic change. Six months later, when her first-born son, Liholiho, heir to the kingdom, was challenged by Kekuaokalani, his cousin, Keopuolani, the only female ali'i kapu (sacred chief), confronted the challenger. She tried to negotiate with him so as to prevent a battle that could end with her son's losing the kingdom. The battle at Kuamo'o was fought, Kekuaokalani was killed, and Kamehameha IPs kingdom was saved. Three months later, the first of the American Protestant missionaries arrived in Kailua, Kona, with a new religion and a system of education. Keopuolani was the first ali'i to welcome them and allowed them to remain in the kingdom. Information about her personal life is meager and dates are few. There is no known image of her, although there was a sketch done of her by the Reverend William Ellis, a member of the London Missionary Society, who lived in the Hawaiian kingdom for two years,

Esther T. Mookini translates for the Judiciary History Center of Hawai'i, Honolulu.

The Hawaiian Journal ofHistory, vol. 32 (1998)

2 THE HAWAIIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY

1822-1823. However, that sketch was lost during the time his Journal of William Ellis was being published in London, sometime between 1825 and 1828. In his Journal there are sketches of people and landscapes as British missionaries were trained in sketching (David Forbes, personal communication, 1997). American Protestant missionaries who came to Hawai'i in 1820 did much writing: letters, papers, accounts, diaries, and journals. They were consistent about writing regularly to their office in Boston and to their friends and families regarding their work. Their sketches were few, mainly of their houses and surroundings. Among these missionaries, some of the wives may have had painting lessons, but the men generally had not even received rudimentary drawing lessons.1 In April 1823 the second company of American missionaries arrived, bringing the Reverend William Richards and the Reverend Charles Stewart. Keopuolani immediately asked that these missionaries accompany her to Lahaina, Maui, where she lived her last five months under their religious guidance, along with Taua, a Christian Tahitian. Richards and Stewart wrote of her conversion to Christianity with deep feeling, that she had indeed shown her desire to be baptized. The two men drew a picture of Keopuolani in words. Samuel M. Kamakau pictured her in Hawaiian words in his articles published in the Hawaiian newspapers, Ka Nupepa Kuokoa, 1866—1869, and Ke Au Okoa, 1869-1870, which were translated by Mary Kawena Pukui and published under the title Ruling Chiefs of Hawaii. William Richards's Memoir of Keopuolani, Late Queen of the Sandwich Islands, published in 1825 in Boston and London and later in France, was to inform the Western nations of the conversion of Keopuolani and that the mission to the Sandwich Islands was on its way to success because of her influence among her people. This information was crucial to Americans and Europeans who had already penetrated the Pacific for political and commercial gain. It was of great significance for them to know that the chiefs in the kingdom were being educated and Christianized. Westerners who came to Hawai'i from 1778 to 1820 were traders, whalers, and those on scientific expeditions sent out by foreign nations. There were artists on board, but they were more interested in sketching landscapes and painting portraits of chiefs, among whom

KEOPUOLANi: SACRED WIFE, QUEEN MOTHER 3

were Ka'ahumanu, Kamehameha, Boki, and Ke'eaumoku but not Keopuolani. Perhaps the Westerners did not notice her because she was not in the forefront of politics and commerce like her sisterqueen, Ka'ahumanu. Perhaps it was because of her kapu moe (prostrating tabu), which prevented people from looking upon her. The written picture of Keopuolani is that of a dutiful child, responsible wife and mother, and a chief who abided by and respected the ancient traditions. She was obedient to the chiefs, her husband, and all people. Her sister-queens spoke of her with admiration due to her mild disposition. She was amiable and affectionate and known to be gentle and considerate, tender and loving, kind and generous. She was strict in the observance of the kapu (tabu) but mild in her treatment of those who had broken it, and they often fled to her for protection. She was said by many of the chiefs never to have been the means of putting any person to death. There is another picture of Keopuolani and that is of her at play. When the Thaddeus arrived in Kailua bay, Kona, the Reverend Hiram Bingham wrote of a great number of people—men, women, and children, from the highest to the lowest rank, including the king and his mother—amusing themselves in the water. They were at Kamakahonu, where a spring, Ki'ope,

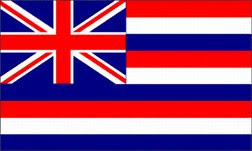

FIG. 1. Funeral procession of Keopuolani. Watercolor sketch by William Ellis. (Hawaiian Mission Children's Society)

4 THE HAWAIIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY

mixes with sea water, a favorite gathering place for swimmers and surfers.2 Three years later, in 1823, she moved to Lahaina, taking her daughter, Nahi'ena'ena, along with missionaries Richards and Stewart and their families, as she was seriously contemplating becoming a Christian. It may have been her relatively unstable physical health throughout her adult life that led her to believe in Christ. In 1806, at Waikiki, she was so ill that Kamehameha thought she was going to die. He offered human sacrifices to restore her health, but before all the victims were sacrificed, she recovered. In the spring of 1823 she was again in poor health. She became more attentive to the Gospel as she was resting. It was Taua who became the teacher she relied on as perhaps they were able to converse with each other in the Polynesian language. Three months later, in the last week of August, she fell very ill. Two weeks later, she was dead. The funeral ceremonies, after the Christian manner, were held two days later with chiefs, missionaries, and foreigners surrounding the corpse. All were respectably dressed in the European style. During the whole time, the most perfect order was preserved.3

KEOPUOLANI'S GENEALOGY

Keopuolani (the gathering of the clouds of heaven), was the highest ranking chief of the ruling family in the kingdom during her lifetime. She was ali'i kapu of ni'aupi'o (high-born) rank, which she inherited from her mother, Keku'iapoiwa Liliha and her father Kiwala'o. Born in 1778 or 1780 at Pahoehoe, Pihana, Wailuku, Maui,4 her name, given at birth, was Kalanikauikaalaneo (the heavens hanging cloudless). She may have been named for her ancestor, Kakaalaneo, who, with his brother, Kakae, ruled Maui and Lana'i from their court in Lele, the ancient name of Lahaina. It was Kakaalaneo who planted the breadfruit trees in Lahaina for which the place became so famous as to be called Malu Ulu o Lele (breadfruit groves of Lele) .5 Kakaalaneo's time as ali'i of Maui was after regular voyages between Hawai'i and the southern islands ceased, and he was named in a chant as the stranger forefather from Kahiki.6 His direct ancestor was Mooinanea, a mythical mo'o 'aumakua (lizard guardian spirit). She was called by

KEOPUOLANI: SACRED WIFE, QUEEN MOTHER 5

other names such as Makuahanaukama (mother of many children) as she was said to have had eleven or twelve children by Kamehameha, but only three survived. She was also called Wahinepio (captive woman), as she was "captured" on Moloka'i by Kamehameha, but she was most commonly known as Keopuolani, a name given to her when she was fifteen or seventeen years old.7 Her ancestors on her mother's side were ruling chiefs of Maui as far back as Kakaalaneo. She was called queen of Maui.8 Her mother

Mo'oinanea

Mythical

Kakalalaneo Kakae

Kahekili I

Kings of Wailuku

Kalamakua = Kelea Kawao Kaohele

Laielohelohe = Pi'ilani Kings of Maui 16th century

Umi-a-Liloa — Pi'ikea Kala'aiheana = Kamalama Lono-a-Pi'ilani Kiha-a-pi'ilani Kihawahine Kuihewakanaloahano = Nihoa Kamalama Kamalawalu (Waiokama)King s of Hawaii

Keawepaikanaka = Maluna Kahakumaka Kualu

Konokaimehelai = Kihalaninui

Hilia = Kamalau I Waiau = Kahiko

Kapao = Haalou

Kauhi-a-Kama 17th Century I Kalani-Kaumakaowakea

Lonohonuakini I Kaulahea

Keku'iapoiwanui 2 Kekaulike 18th Century

Keku'iapoiwa II = Keoua = Kalola = Kamehamehanui Kahekili II Kauhiaimokuakama Kamae — 'Aikanaka

Keohokalole = Kapa'akea Kamehameha I = Keopuolani

Kalanikupule Kalanikauiokikilo-kalani-akua Kalani'opu'u

Keku'iapoiwa Q Kiwala'o Liliha I

19th century

Liholiho Kauikeaouli Nahi'ena'ena

Kalakaua Lili'uokalani, etc.

Kings of the Hawaiian Islands

mo'o Q pi'o or ni'aupi'o

FIG. 2. The genealogy of Keopuolani. From P. C. Klieger, ed., "Mokuula, History and Archaeological Excavations" (Bishop Museum, 1975), p. 2.

6 THE HAWAIIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY

was named after her great-grandmother, Keku'iapoiwanui, wife of Kekaulike, the paramount chief of Maui. The children of Keku'iapoiwanui and Kekaulike were Kalola Pupukaohonokawailani, ali'i kapu of Maui and Hawai'i, and her brother, Kahekili, ruling chief of Maui and O'ahu. Kalola lived with two brothers, Kalani'opu'u and Keoua, both Hawai'i island ni'aupi'o chiefs. From Kalani'opu'u, the older brother, she had a son, Kalanikauikeaouli Kiwala'o, more often called Kiwala'o. From Keoua, the younger brother, she had a daughter, Keku'iapoiwa Liliha. The children, Kiwala'o and Keku'iapoiwa, had the same mother, different fathers, offspring of a naha union. These two lived together, and Keopuolani was born, the offspring also of a naha union. She was their only child who inherited her ni'aupi'o rank from both parents. A ni'aupi'o chief was of very high rank, and this rank was passed from a ni'aupi'o chief to his or her children. They could never lose that rank. Chiefs of ni'aupi'o and pi'o ranks from naha unions were considered the most sacred of all high chiefs, and these unions were carried out to assure succession to royal power and to obtain the intensified mana important to community and family life.9 Her ancestors on her father's side were of the blood of chiefs who had ruled the island of Hawai'i for as many generations back as the genealogies extend. Her father was Kiwala'o, his father was Kalani'opu'u, and his father was Kalaninuiiamamao, the first-born of the ruling chiefs over all Hawai'i island. Keopuolani's and her ancestors' genealogies were called Kumuuli and Kumulipo, which are found in the song of the kapu chiefs of O'ahu—Kualii, Peleioholani, and Kahahana. The genealogy of Kumuuli, which was much praised by the ancient Hawaiian chiefs and quoted in the famous chant of Kualii, the warrior king of O'ahu, was recited in honor of Keopuolani, who was the kapu descendant of the Maui line of kings. The O'ahu chiefs have no direct descendants in this world; their genealogies trace back through the ancestors of Keopuolani, who bore Kamehameha II and Kamehameha III.10 There were nine traditions that emphasized chiefly rank: one was having a family genealogy tracing back to the gods through Ulu or Nanaulu. Keopuolani's genealogy traced back to Ulu, who descended from Hulihonua and Keakahulilani, the first man and woman created by the gods. Another tradition was that a name chant be composed at birth or given in afterlife, glorifying the family history.11

KEOPUOLANi: SACRED WIFE, QUEEN MOTHER 7

Kiwala'o was present at the birth of Keopuolani as he and his wife were visiting her brother, Kahekili, who, at that time, was the king of Maui, Lana'i, Moloka'i, and O'ahu. Soon after the birth of his daughter, Kiwala'o returned to Hawai'i to become ruling chief over that island. The child remained on Maui as she was hdnai (brought up) in Wailuku, Olowalu, and Hamakua by her maternal grandmother, Kalola. It was not customary for the chiefs to bring up their own children.12

KEOPUOLANI'S CHILDHOOD

Keopuolani was reared under strict kapu because she was sacred; her kapus were equal to those of the gods. At the time she was being nursed by her wet nurse, neither chief nor commoner dared approach or touch her; anyone who disobeyed this kapu was burned to death. She possessed kapu moe, which meant that those who were in her presence had to prostrate themselves, face down, for it was forbidden to look at her. At certain seasons, no person was allowed to see her. In her childhood and early adulthood, she never walked out during daylight hours. The sun was not permitted to shine upon her. As a result, extraordinary precautions had to be made before she could move about, and this she did only after the sun was so low as not to shine on her. Should her shadow fall on anyone, that would mean his immediate death. Should it fall on the ground, that ground would be kapu, and so she chose to be among people at night. She did this for the benefit of the people and was known to be gentle and considerate. The ordinary people did not ever see the chiefs because of their kapu, and those chiefs of the highest rank were named for a god or by lani (heaven), where the gods lived.13 Keopuolani's grandfather, Kalani'opu'u, was an old man and was not expected to live many years longer. He called a council of chiefs in Waipio valley, and there he designated his son, Kiwala'o, his successor, based on his ni'aupi'o rank, which came from his mother, Kalola.14 Kalani'opu'u died about four years after Keopuolani's birth. His bones were taken by his sons, Kiwala'o and Keoua, who were accompanied by their uncle Keawemauhili, the cousin Kamehameha, chiefs of Kona, and other chiefs and were deposited in Hale o Keawe at Honaunau, Kona. There the distribution of land was made, with

8 THE HAWAIIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY

Keawemauhili having his way to the disadvantage of Kiwala'o and Keoua, as well as Kamehameha and the Kona chiefs. But when battle lines were drawn, it was Kiwala'o, Keoua, and Keawemauhili against Kamehameha and the Kona chiefs. The actions of Kiwala'o and his brother were illogical. The only rational explanation of their course appears to be that a plan had been prearranged between the uncle and the two brothers to provoke a quarrel with Kamehameha and the Kona chiefs, defeat them in battle, and strip them of their possessions. In the battle of Moku'ohai in 1782 Kamehameha and the Kona chiefs were victorious.15 When Kiwala'o was killed, Kalola, her daughters Keku'iapoiwa and Kalaniakua, and her granddaughter, fouryear-old Keopuolani, fled to Maui, for they had taken refuge with her brother, Kahekili, and his son, Kalanikupule.16 The victory at the battle of Moku'ohai was the start of Kamehameha's rise to power. The island was divided into three kingdoms: Kamehameha held Kona, Kohala, and the northern part of Hamakua; Keoua held Ka'u, and part of Puna; Keawemauhili held Hilo and took parts of Hamakua and Puna. For nearly four years the three kingdoms on Hawai'i island were at peace. The first recorded foreigner in Hawaiian waters was Captain James Cook, who came in January 1778, the year Keopuolani is said to have been born. He was killed at Kealakekua in January 1779. After his ships left, no foreign ships are known to have visited Hawai'i until 1786, when two British and two French naval vessels came, opening the Islands to European nations, which saw them as a place for colonization or for the promotion of commerce.17 The American trading ships Ekanora and Fair American came into Hawaiian waters in 1790. Kamehameha took possession of the Fair American and at the same time acquired the services of American sailors John Young and Isaac Davis. Armed with a Western ship, guns, and two Western advisors, Kamehameha decided to attack Maui as Kahekili's forces would be no match for his new weapons. Twelve-year-old Keopuolani, her mother, and her aunt were with Kahekili when the battle of Kepaniwai (the damming of the waters) was fought in Tao Valley, Wailuku. Kamehameha' s men destroyed the Maui forces, whose bodies dammed up the water of the Wailuku (water of destruction), hence perhaps the name of the river.18

KEOPUOLANK SACRED WIFE, QUEEN MOTHER 9

KEOPUOLANI'S "CAPTURE" BY KAMEHAMEHA

Kalanikupule, Kahekili's son, and some of his chiefs escaped to O'ahu. Keopuolani, her mother, Keku'iapoiwa, and her aunt, Kalaniakua, fled over the pass in 'Iao valley to Olowalu, where they joined Kalola and all escaped to Kalama'ula, Moloka'i. They could not continue on to O'ahu to be under the protection of Kalola's brother, Kahekili, because Kalola was too ill to travel any further. Kamehameha could have gone after Kahekili on O'ahu, but he felt it would be sound policy to make peace with Kalola and try to get her two daughters and granddaughter in his possession. He sent a messenger to Kalola asking her not to go on to O'ahu but to go with him back to Hawai'i island, where she and her daughters and her granddaughter would be provided for as became their high rank. Kamehameha took a great company to Moloka'i, among them Kame'eiamoku and Kamanawa, twin brothers of Kalola. When they landed at Kaunakakai, they were told that Kalola was very sick and not expected to live. He went at once to her and asked her: "Since you are so ill and perhaps about to die, will you permit me to take my royal daughter and my sisters to Hawai'i to rule as chiefs?" Kamehameha called Keopuolani his daughter because Kamehameha had grown up with Kalola's son, Kiwala'o, and the two were as brothers.19 Ii stated that Kamehameha and Kiwala'o shared Keku'iapoiwa, and in that way he saw himself as Keopuolani's father.20 Kamehameha referred to Keopuolani as his kaikamahine (daughter or niece), and when their children, Liholiho, Kauikeaouli, and Nahi'ena'ena were born, he called them his grandchildren in respect to their lineage as chiefs.21 Agreeing to Kamehameha's offer, Kalola was doing what Hawaiian women had always done, that is, controlling not only their own reproductive potential but also that of their daughters and granddaughters because children were their most important product.22 She knew, too, that Kamehameha, an aspiring ruler, needed to produce children by the highest ranking woman, and that woman was her granddaughter, Keopuolani. When Kalola died, Kamehameha and all the chiefs wailed and chanted dirges; the chiefs tattooed themselves and knocked out their teeth.23 When the mourning period was over and Kalola's bones were deposited in a secret cave in Kaloko, Kekaha, Hawai'i, Kamehameha

1O THE HAWAIIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY

took charge of her two daughters and her granddaughter, not only as a legacy from the mother but as a seal of reconciliation between himself and the representatives of Kiwala'o, the Keawe dynasty.24 This "capture" of the women by Kamehameha, a conquering chief taking the widow and female relatives of his defeated rival, was politically important. Most noteworthy was the manner in which he "captured" them, asking a high-ranking chiefess for the women and going to great lengths to pay respect to her; not using force and addressing only Kalola, the female head of the matriline; and following the rules of conduct during the mourning period.25 Kamehameha fully recognized that Keopuolani was, among all the chiefesses, the only heir to the nine traditions that emphasized her rank. One such tradition was regarding genealogy, another was a chant at the birth or death of a chief glorifying the family history, and another was the power of the kapu, which certain chiefesses of Maui (Kalola, her two daughters, and her granddaughter) of incredible sanctity possessed and before whom all had to remove their garments.26 Kamehameha knew too that she was descended directly from Kihawahine, the powerful Maui mo'o 'aumakua, which he needed to have in his assemblage of gods if he was to succeed in conquering the Islands. He believed, as others did, that the kingdom that cared for (malama) Kihawahine prospered. He already possessed the war god Kuka'ilimoku (land snatcher) and now by his "capturing" Keopuolani, he acquired Kihawahine (land holder). He knew too that his children from Keopuolani would further tie the senior line of Hawai'i tightly with that of the prestigious Piilani lineage of Maui as it had before when Kalola of Maui married Kalani'opu'u, Hawai'i chief, and before them when Piikea, Maui chiefess, married Umialiloa, Hawai'i chief. His children would inherit the superior ni'aupi'o rank and be associated with Kihawahine through their mother, Keopuolani. In obtaining these women, Kamehameha also adopted Kihawahine.27 Kamehameha's wives came mainly from Maui since the chiefs of Hawai'i and Maui were closely related.28 His first wife was Kalolaakumukoa, daughter of Moloka'i chief Kumukoa. He had her before the battle of Moku'ohai, before he gained prominence. They had no children. He was also married to Kanekapolei, who bore him his first

KEOPUOLANi: SACRED WIFE, QUEEN MOTHER 11

child, a son, Ka'oleioku, but he did not appear in line to succeed his father. Peleuli, an aunt of Keopuolani, became another of his wives. Ka'ahumanu, first-born of Ke'eaumoku, the most beautiful woman in Hawai'i in those days, became his wife in 1785. She was treated with utmost respect but not given ceremonial kapu, which would have been hers if she were ali'i kapu. In 1789 Kamehameha deserted Ka'ahumanu for a while and lived entirely with Kaheiheimalie, Ka'ahumanu's sister, who was already married to Kamehameha's brother and who matured into a beautiful woman after bearing a child, much to the grief of Ka'ahumanu, who had been his favorite wife. There was no woman of his household whom Kamehameha loved as much as he did Kaheiheimalie. Kahakuha'akoi, or Wahinepio, sister of Kalanimoku and Boki, was Kamehameha's third favorite wife, after Ka'ahumanu and Kaheiheimalie. Another of Ka'ahumanu's sisters, Piia or Kekuaipiia, sometimes called Namahana, was also his wife. In his old age he brought two young chiefesses, Kekauluohi and Manono, into his household. Eight of these wives traced their descent to Kekaulike, Maui chief.29 When Keopuolani was "captured" by Kamehameha she was about ten or twelve years old. She, her mother, and her aunt were taken to live in Keauhou, North Kona. Keopuolani was celebrated for her beauty, and because she was "captured," she was then called by the name Wahinepio (captive woman). Vancouver wrote in his Voyages a description of a hula that he attended near Kealakekua Bay: 'The piece was in honour of a captive princess whose name was Kalanikauikaalaneo" (Keopuolani's name in her childhood). This was a farewell hula in honor of Vancouver danced by the a/i'iwomen. The hula was the story of the captured Maui child, Keopuolani, who possessed the most powerful kapu. As the dancers told her story, even at the mere mention of her name, although she was on the other side of the island, the audience—chiefs and commoners alike—had to remove all ornaments and clothing above the waist. Ka'ahumanu and Kamehameha would have had to do the same had they been present. 30 In 1795 Kamehameha attacked O'ahu at the battle of Nu'uanu. Keopuolani, who was about seventeen or eighteen years of age, and her mother accompanied Kamehameha when he fought and was vie

12 THE HAWAIIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY

torious over Kalanikupule. Richards said: "Her person was seen as so sacred that her presence did much to awe the enemy." Valeri stated that "an ali'i having the kapu moe can always end a battle by becoming visible and thus forcing everyone to throw down his weapons and fall prostrate."31 It was here that an O'ahu chief gave her the name Keopuolani, by which she was known until her death. It was also perhaps at this time that she was formally hodo (united) with Kamehameha in Waiklki. She was not his constant companion, for he slept with her only from time to time in order to perpetuate the high chiefly blood of the kingdom, which his children from her would inherit. 32 In 1797 she gave birth to a son, Kalani Kua Liholiho. Kamehameha wanted Keopuolani to go to O'ahu, to Kukaniloko, a famous birthing site and heiau (place of worship). Kukaniloko was another of the nine traditions that emphasized rank. Keopuolani was too ill to travel, however, and so gave birth to their first-born child in Hilo. Liholiho was taken by Ka'ahumanu, his hdnai mother, to be brought up in the presence of his father, the ruling chief. Keku'iapoiwa, Keopuolani's mother, and Kalaniakua, her aunt, were also constantly taking part in the child's upbringing.33 On March 17, 1814, Kauikeaouli, her second son, was born in Keauhou, North Kona. She named him after her father, Kalanikauikeaouli Kiwala'o. The baby was adopted (hdnai) by chief Kaikio'ewa. The following year, her daughter, Nahi'ena'ena, was born. Keopuolani loved her children and wept when her two sons were taken away from her, to be brought up by other chiefs. When Nahi'ena'ena was born, Keopuolani would not give her up.34 While Kamehameha was still alive he allowed Keopuolani to have other husbands after she gave birth to his children, a practice common among ali'i women, except Ka'ahumanu. Kalanimoku and Hoapili were her other husbands. Kalanimoku held the highest position in the kingdom as treasurer, regent, chief counselor, and supreme war leader. He had power over the laws of life and death and over Kamehameha's daughters, sisters, cousins, and other chiefesses, who were free to him as wives. Hoapili was a loyal counselor related to the Maui chiefs. His father was Kame'eiamoku, one of Kamehameha's most trusted generals. It was a great honor for Hoapili to guard the ruling kapu family of Hawai'i.35

KEOPUOLANI: SACRED WIFE, QUEEN MOTHER 13

KEOPUOLANI AND THE END OF THE KAPU SYSTEM

Kamehameha died on the night of May 8 or 14, 1819, at Ramakahonu, Kailua, Kona, where he had established his residence six years earlier.36 The following morning, Liholiho and his company of chiefs left Kailua for Kawaihae, Kohala, because the district of Kona was considered to be denied until the corpse was dissected, the bones tied in a bundle, and rites performed to transfigure the dead king into an 'aumakua, a deified ancestor.37 Kumdkena was a period of mourning that followed the death of a very high chief during which people wailed, knocked out their teeth, lacerated their bodies, and at last fell into universal prostration. Also 'ai kapu (foods that were kapu throughout the year) were 'ai noa (foods free of kapu) .38 In the afternoon following the night Kamehameha died, Keopuolani ate coconuts and took food with men which were kapu to women. She said: "He who guarded the god is dead, and it is right that we should eat together freely." This 'ai noa was observed as a part of kumdkena. Kekauluohi, another of Kamehameha's wives, and other female chiefs even tasted pork without being destroyed by the gods. This 'ai noa took place only among chiefs and did not extend to the country districts.39 It was instigated by the female chiefs, specifically the widows, Keopuolani, Ka'ahumanu, her two sisters, Kaheiheimalie and Piia, and Kekauluohi. Keopuolani, the last of the ali'i kapu, was particularly responsible, and it was through her action alone that the 'ai kapu ended.40 In the past, when kumdkena ended, the new ruling chief would place the land under a new kapu following old lines. It was believed that if the new ruling chief did not put a kapu on ' ai noa, he would not have a long rule. He would be looked upon as one who did not believe the god, Kuka'ilimoku. It was further believed that should the ruling chief keep up the ancient kapu and be known to worship the god, he would live long, protected by Ku and Lono, a ward of Kane and Kanaloa, sheltered within the kapu. 'Ai kapu was a fixed law for chiefs and commoners, to keep a distinction between things permissible to commoners and those dedicated to the gods. 'Ai kapu belonged to the kapu of the god; it was forbidden by the god and held sacred by all.41 In the old days kumdkena, at the death of a ruling chief who had been greatly loved, was a time of license. 'Ai noa became an

14 THE HAWAIIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY

established fact and it was the ruling chiefs who established that custom. 'Ai noa as it occurred in 1819 was something Liholiho allowed as he was merely continuing the practice established by earlier chiefs.42 When kumakena came to an end, the necessary ten days for the cleaning of Kamehameha's bones, Hoapili, who had been chosen by Kamehameha himself to put his bones in a place that would never be disclosed to anyone, went with his wife, Keopuolani, by canoe and placed the bones in a secret cave in Kaloko together with the bones of Kalola, Kahekili, and Keku'iapoiwa.43 Fifteen days later, when the funeral ceremonies were completed and the land purified, Liholiho was allowed to return to Kailua, Kona, to be received officially as the new king. His appointment as heir to the throne had taken place in 1804, when he was five years old. At that time, he was in Honolulu with his father, who was preparing to launch an attack on Kaua'i. That was the first time Liholiho was given the kapu of the heiau in which Kamehameha made him the head of the worship of the gods. There was another time when Kamehameha proclaimed Liholiho heir to the kingdom when he was still in possession of all his faculties. At that time, he gave his war god, Kuka'ilimoku, to Kekuaokalani, his favorite nephew, who was constantly at his side. It was then that Kamehameha taught the two boys the history of the government and of the god, that the two were of equal importance in ancient days. The last time he gave his kingdom to Liholiho was when he was coming to the end of his life. He announced before the chiefs and people that Liholiho was to be the heir to the kingdom after his death and the god to go to Kekuaokalani, his second heir.44 The installation ceremony, which took place at Kamakahonu, Kailua, Kona, was a stunning sight. A group of chiefs, radiant in feather cloaks and helmets, with Ka'ahumanu in the center, faced the people. Into this assemblage came Liholiho, a superb figure, who walked out of Ahu'ena heiau, dressed in great splendor wearing a suit presented him from England with a red coat trimmed with gold lace and a gold order on his breast, a feather helmet on his head, and a feather cloak worn over his shoulders. He was accompanied by two chiefs carrying his kahili (feather standards). As he approached the circle of chiefs, he was met by Ka'ahumanu, who said: "O heavenly one! I speak to you the commands of your grandfather. Here are the chiefs,

KEOPUOLANi: SACRED WIFE, QUEEN MOTHER 15

here are the people of your ancestors, here are your guns, here are your lands. But we two shall share the rule over the land."45 Liholiho assented and became ruling chief with the title Kamehameha II and Ka'ahumanu, co-ruler with the title kuhina nui. Some of the people did not like Ka'ahumanu's use of the word "grandfather" when she spoke the chiefs commands, but it was true that Kamehameha never called Liholiho his child but his grandson. Ka'ahumanu, wearing her feather cloak and feather helmet, leaning on the spear of Kamehameha, made a plea for religious tolerance. She said:

If you wish to continue to observe my father's [Kamehameha's] laws, it is well and we will not molest you. But as for me and my people we intend to be free from the tabus. We intend that the husband's food and the wife's food shall be cooked in the same oven and that they shall be permitted to eat out of the same calabash. We intend to eat pork and bananas and coconuts. If you think differently you are at liberty to do so; but for me and my people we are resolved to be free. Let us henceforth disregard tabu.46

No other chief would have dared to make such a declaration in public. The king remained silent and withheld his consent. Keopuolani looked at her son, the new king, and put her hand to her mouth as a sign for 'at noa. He made no response. She saw no signs of concession from Liholiho. She was then deeply moved with aloha for Ka'ahumanu. Since Ka'ahumanu's proposal was refused, Keopuolani was certain that when Ka'ahumanu carried out her intentions, the extreme vengeance of violated kapu would annihilate her sisterqueen. It was then that Keopuolani sent for Kauikeaouli, her fiveyear-old son, and in the late afternoon she ate with him in defiance of the kapu.47 Keopuolani, the only remaining ali'i kapu, took this monumental step to free the 'ai kapu perhaps to save Ka'ahumanu from the wrath of the gods. Because Keopuolani, a ni'aupi'o chief, was always looked upon as divine, her kapu?, equal to those of the gods, she may have felt that the gods would not harm her but that they would certainly destroy Ka'ahumanu, who was not an ali'i kapu. Not all the chiefs joined in the revolution. One chief in particular, Kekuaokalani, who did not attend the ceremony installing Liholiho as the new king, tried to keep Liholiho from going to Kailua, where

l6 THE HAWAIIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY

'ai noa was taking place, because he feared that should Liholiho be contaminated by 'ai noa, the gods would perhaps even destroy the new king. He said to Liholiho: "Your grandfather [Kamehameha] left commands to the two of us that the care of the government was yours and that of the god was mine and each of us to look to the other."48 Liholiho was in a dilemma. He could go with his two mothers, Keopuolani and Ka'ahumanu, and take part in 'ai noa, which was only a symbol for the abandonment of the old system, or go with Kekuaokalani and uphold the ancient religion and tabu. Liholiho consulted with Hewahewa, the kahuna nui (high priest), who told him that it would be a good thing to abolish the kapu and abandon their gods.49 Liholiho then agreed to go with his two mothers, along with Kalanimoku, to abolish the whole kapu system as soon as it could safely be done. It was necessary for the young king to ensure the safety of his throne. In these deliberations, the two mothers took the leading part, and their opinions were seriously considered. Hawaiian ideology embodies a high regard for women in certain statuses, particularly that of mother, for she is the receptacle in which and through which things have life, growth, and reproduction. The mother/son relationship is consistently characterized in myths, proverbs, and chiefly legends as solidary, supportive, and affectionate.50 In the first week of November 1819, six months after his installation as Kamehameha II, Liholiho finally made his decision regarding 'ai noa. He returned to Kailua after staying in Kohala those six months and made preparations for a feast to take place in a large building near Ahu'ena heiau to which all the leading chiefs and foreigners were invited. This was only after he had secretly consulted with Hewahewa and the principal chiefs upon the subject of 'ai noa and after they had given their consent and cooperation. Two tables were set up with chairs, one for the men and the other for the women. After the guests had been seated, the king rose and said to John Young: "Cut up those fowls and that pig." Then he went to the women's table, sat down with his mothers, and began to eat in a fury, realizing that he was doing violence to himself but determined to overcome what he had always done, 'ai kapu. Seeing this, the guests cried out: "Ai noa— the eating tabu is broken." Then Liholiho directed that men and women throughout the kingdom were free to eat together and share

KEOPUOLANi: SACRED WIFE, QUEEN MOTHER 17

equally of foods prohibited to women. Hewahewa ordered that all heiau be destroyed, and he himself went out and burned an adjoining heiau. Messengers were sent to Maui, Moloka'i, O'ahu, and all the way to Kaua'i with the order: "Make eating free over the whole kingdom from Hawaii to Oahu and let it be extended to Kauai!" Boki of O'ahu and Kaumuali'i of Kaua'i consented.51 Kekuaokalani saw this as a most wicked offense by his cousin because the destruction of the gods and the heiau not only abolished his power but also that of the kahuna and his role in the heiau. Kekuaokalani took a stand at Ka'awaloa, refusing to join Liholiho because he felt that Liholiho, the government, and he, the guardian of the god, were going on separate and opposite paths. Kalanimoku then sent out two chiefs, Naihe and Hoapili, uncles of Kekuaokalani, to try conciliatory measures first and bring him back to Kailua in order to avoid battle. Just as the two chiefs stepped into their canoe, Keopuolani joined them. No one knew of her intentions to go to Kekuaokalani. In doing what she did, she became the cause for the battle of Kuamo'o, because as the living representative of the gods on earth, she sent a message to him that 'ai kapu was abolished. The battle took place at the end of December 1819. Kekuaokalani was the last of the high chiefs who posed a barrier not only to Keopuolani's and Ka'ahumanu's newly developed power but, more importantly, their son's reign. At Kuamo'o, Kekuaokalani had fewer men and even fewer weapons than Kalanimoku's forces. Kekuaokalani's men were driven to the sea where they were exposed to a fleet of double canoes, one, a peleleu (canoe fitted with a mounted swivel gun) under the charge of a foreigner, perhaps John Young, commanded by Ka'ahumanu and her sister, Kalakua. Kekuaokalani was killed and his followers were put down. The old religion, as an organized system, was abandoned. The old tabus were no longer enforced.52 The year ended with the kingdom secure in the hands of Liholiho, Kamehameha II. A new office, the kuhina nui, was created, which made his hdnai mother, Ka'ahumanu, a co-ruler. This was the first time in the kingdom's history that a woman occupied such a high position. At the same time came the abolishment of the ancient kapu system, which the female chiefs had long desired, liberating them to

l8 THE HAWAIIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY

eat certain foods and enter sacred places authorized by the male chiefs. The end of the kapu system brought about the end of the state religion, the end of the worship of Ku in the form of Kuka'ilimoku, the god of male chiefs. The female chiefs, with their newfound power, replaced the old religion with a new one that came four months later.

KEOPUOLANI AND THE MISSIONARIES

On March 3, 1820, the Thaddeus, with the first company of American Protestant missionaries aboard, anchored at Kawaihae. Here they learned of the death of Kamehameha, the ascension of his son, Liholiho, as the new king, the end of the kapu system, and the abolishment of the heiau, and with it, the class of kahuna. Since the new king and his chiefs were in Kailua, the missionaries went to him, coming ashore at Kailua, Kona, on April 4. Liholiho did not give them an immediate reply to their request to reside in the kingdom and carry on their work. The missionaries walked along the beach at Kamakahonu, followed by a crowd of curious people. They continued to walk until they came to Oneo to visit Keopuolani. There they were received by the queen mother, and they exchanged greetings with her. Keopuolani no longer possessed kapu moe as her dreaded kapu ended with 'ai noa. Thomas Hopu, one of the four young Hawaiian men who had come with the missionaries, was the interpreter. She was the first ali'i who welcomed the missionaries and without hesitation approved their proposals. It was Hopu from whom she first heard the word of God and from whom her two children, six-year-old Kauikeaouli and four-year-old Nahi'ena'ena, first learned letters. She herself was not interested in the pule (new religion) but favored the palapala (system of instruction) ,53 In September Liholiho was advised by his chiefs to move to Honolulu due to its growing importance. By February 1821 his household, which included five wives, his mothers Keopuolani and Ka'ahumanu, and Kalanimoku and a group of chiefs, was settled in Honolulu. In early July Liholiho proposed a trip to Kaua'i. The chiefs advised him to protect himself by sailing with a large group, but Keopuolani said: "Do not be afraid and do not take the men with you for you will find men on Kauai." When Liholiho and his company of wives and a few

KEOPUOLANi: SACRED WIFE, QUEEN MOTHER ig

friends arrived on Kaua'i, they were welcomed with great affection by Kaumuali'i. Soon after, other chiefs, among them Keopuolani and Hoapili, accompanied by Ka'ahumanu and her brother Ke'eaumoku, also went to Kaua'i, and Kaumuali'i graciously received them.54 Here Keopuolani met the missionaries Samuel Whitney and Samuel Ruggles. When she returned to O'ahu, she met Hiram Bingham, took her stand as a Christian, and gave up drinking. The following spring, on April 11, 1822, the Reverend William Ellis, an English missionary, arrived from Tahiti with several Christian Tahitian teachers. She took these Tahitians to be her teachers as she was more able to understand Tahitian than English. They taught her to read and write and held religious services mornings and evenings.55

KEOPUOLANI'S CONVERSION

In February 1823 Keopuolani and Hoapili chose Taua, one of the Tahitian teachers, to instruct them and their people in the pule and the palapala. She asked him for advice about her having two husbands. He answered: "It is proper for a woman to have one husband, man to have one wife." She then said: "I have followed the custom of Hawaii, in taking two husbands in the time of our dark hearts. I wish now to obey Christ and to walk in the right way. It is wrong to have two husbands and I desire but one. Hoapili is my husband, hereafter my only husband." To Kalanimoku she said: "I have renounced our ancient customs, the religion of wooden images, and have turned to the new religion of Jesus Christ. He is my King and my Savior, and him I desire to obey. I can have but one husband. Your living with me is at an end. No more are you to eat with my people or lodge in my house."56 On April 28, 1823, the second company of American missionaries arrived in Honolulu. They walked to Waikiki by the seaside, where the chiefs were. Keopuolani and the rest of the chiefs welcomed the new missionaries. Among them were the Reverend William Richards and the Reverend Charles Stewart. In May Keopuolani decided to move to Maui, land of her birth. Hoapili, her husband, had just been named governor of that island. She chose to live in the beachfront area called Kaluaokiha in Lua

2O THE HAWAIIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY

'ehu, Lahaina. Lua'ehu was noted for its freshwater springs. Food plants were everywhere: huge lo'i kalo (taro patches) were between her house and the residences of the missionaries; breadfruit trees with fish ponds beneath them and coconut trees and rows of sugar cane grew abundantly. The beach stretched for more than a mile, lined with houses and shaded by kou and coconut trees. The surf of 'Uo was well known, and chiefs from the ancient days had always come here to ride the waves. Keopuolani had her house built on the beach with her daughter, Nahi'ena'ena, living in her own home next door called Hale Kamani. When Keopuolani sailed to Maui, taking Richards and Stewart with her, she told them that they would be her sons and that she would look after them, which she did. As soon as they arrived, she sent cooked food for that day as well as for the next day, which was the Sabbath.57 She requested that they start teaching her immediately at morning and evening prayers. The next day, June 1, Monday, Richards and Stewart began their work in the houses of Keopuolani and Hoapili, Nahi'ena'ena, Kekauonohi, Liholiho's wife, and Wahinepio, another of Kamehameha's widows. On June 3 Kalanimoku returned to Honolulu. The only reason for his going to Lahaina was to escort Keopuolani as she was the highest ranking chief and still received

FIG. 3. Lamentation on the death of Keopuolani. From C. S. Stewart, Journal of a Residence in the Sandwich Islands. (Hawaiian Mission Children's Society)

KEOPUOLANi: SACRED WIFE, QUEEN MOTHER 2 1

every honor and affection from the chiefs and people. He told Richards and Stewart that the queen mother would continue to look after their needs as she had done. Three months later, in the last week of August, she fell ill again and this time she had a premonition of her approaching death. Whenever any of the chiefs became ill, all the chiefs throughout the kingdom were called to go to that chief. They began to gather in Lahaina. Keopuolani asked especially for Liholiho and the O'ahu chiefs to come. In two weeks her condition worsened. In early September she became seriously ill. Dr. Abraham Blatchely, who came with Richards and Stewart in the second company of missionaries, was summoned from the Honolulu mission to see her, and he said that she was not going to recover. During her last week of life she was concerned with the welfare and rearing of her two young children, nine-year-old Kauikeaouli and eight-year-old Nahi'ena'ena. She ordered Hoapili and Kalanimoku to be sure that Nahi'ena'ena be instructed in the palapala and that she learn to love God and Jesus Christ. She said to Kalanimoku:

Jehovah is a good God. I love him and I love Jesus Christ. I have no desire for the former gods of Hawaii. They are all false. When I die, let none of the evil customs of this country be practiced at my death but let my body be put in a coffin. Let me be buried in the ground and let my burial be after the manner of Christ's people.

She instructed Liholiho to be a friend to his father's friends, to her friends, and to the missionaries and to take good care of the lands he had received from his father and to take good care of the people. Then she said to Ke'eaumoku: "Let it never be said that I died by poison, by sorcery, or that I was prayed to death, for it is not so."58 Her life was coming to an end and she had not yet been baptized. The Reverend William Ellis was summoned because the missionaries knew that the queen would be most comfortable with his instructions regarding baptism in Tahitian. He was taken to the queen mother, and after he explained the meaning of baptism to the royal family and chiefs, he then sprinkled Keopuolani with water, baptizing her in the name of God and calling her Harriet, the name Keopuolani took to be her baptismal name, which was Mrs. Stewart's name. One hour later, at six in the evening, the queen was dead.59

22 THE HAWAIIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY

The next morning, ships in Lahaina roads, with their flags at half mast, fired their guns at regular intervals throughout the day. A Hawaiian flag, at half staff, was set up in front of the house where she died. Liholiho asked if wailing for the dead queen would be wrong. Having been told that it was not, he, with all the chiefs, joined in loud wailing. They did not stop until the day of the funeral, which took place two days later.60 On September 18 Keopuolani, at forty-five years of age, was laid to rest in a substantial mud-and-stone house just built by Nahi'ena'ena at Hale Kamani, Nahi'ena'ena's residence at Kaluaokiha, Lua'ehu, Lahaina.61

NOTES 1 David Forbes, Encounters with Paradise: Views of Hawaii and its People 1778—1941 (Honolulu: Academy of Arts, 1992) 86. 2 Rufus Anderson, History of the Mission of the ABCFM (Boston: Congregational Publication Board, 1874) 61; Dorothy B. Barrere, Kamehameha in Kona, Two Documentary Studies, Pacific Anthropological Research no. 23 (Honolulu: B. P. Bishop Museum, 1975) 2. 3 Paul C. Klieger, ed. "Mokuula, History and Archaeological Excavations at the Private Palace of King Kamehameha III in Lahaina, Maui" (Honolulu: Bishop Museum Anthropology Dept., 1995) 36—37. 4 Samuel M. Kamakau, Ruling Chiefs of Hawaii (Honolulu: Kamehameha Schools P, 1961) 259; William Richards, Memoir of Keopuolani Late Queen of the Sandwich Islands (Boston: Crocker & Brewster, 1825) 9. 5 Abraham Fornander, Account of the Polynesian Race: Its Origins and Migrations (Reprint, Rutland, Vt.: Charles E. Tuttle, 1969) 2: 82. 6 Martha W. Beckwith, Hawaiian Mythology (Honolulu: U of Hawai'i P, 1970) 384-86. 7 Richards, Memoir 13; Jocelyn Linnekin, Sacred Queens and Women of Consequence: Rank, Gender, and Colonialism in the Hawaiian Islands (Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1990) 62-63. 8 William Ellis, Journal of William Ellis (Reprint, Honolulu: Honolulu Advertising Co., Ltd., 1962) 43. 9 Kamakau, Ruling Chiefs 263; Samuel M. Kamakau, Ka Poe Kahiko, The People of Old (Honolulu: Bishop Museum P, 1964) 4—5; Mary Kawena Pukui and Samuel H. Elbert, Hawaiian Dictionary (Honolulu: U of Hawai'i P, 1986) 258, 265, 331; Cummins E. Speakman, Mowee, An Informal History of the Hawaiian Island (Salem: Peabody Museum, 1978) 83. 10 Kamakau, Ruling Chiefs 76, 259, 433-36; Fornander, Polynesian Race 1: 184. 11 Beckwith, Hawaiian Mythology 377.

KEOPUOLANI: SACRED WIFE, QUEEN MOTHER 23

12 Richards, Memoir 11. 13 Kamakau, Ka Poe Kahiko 10. 14 Kamakau, Ruling Chiefs 118. 15 Ralph S. Kuykendall, The Hawaiian Kingdom. Vol. l. 1778—1854. Foundation and Transformation (Honolulu: U of Hawai'i P, 1938) 33. 16 Kuykendall, Hawaiian Kingdom 35; Kamakau, Ruling Chiefs 148. 17 Kuykendall, The Hawaiian Kingdom 21. 18 Mary K. Pukui, Samuel H. Elbert, and Esther T. Mookini, Place Names of Hawaii (Honolulu: U of Hawai'i P, 1984) 109. 19 Kamakau, Ruling Chiefs 149; Kuykendall, Hawaiian Kingdom 35. 20 John Papa Ii, Fragments of Hawaiian History (Honolulu: Bishop Museum P,

1959) 152. 21 Kamakau, Ruling Chiefs 220n. 22 Linnekin, Sacred Queens 58. 23 Kamakau, Ruling Chiefs 149; Fornander, Polynesian Race 2: 238. 24 Fornander, Polynesian Race 2: 238. 25 Linnekin, Sacred Queens 63. 26 Beckwith, Hawaiian Mythology 377. 27 Klieger, "Mokuula" 21-23; Kamakau, Ka Poe Kahiko 85. 28 Kamakau, Ruling Chiefs 68. 29 Kamakau, Ruling Chiefs 109, 184, 208, 311; Linnekin, Sacred Queens 64. 30 Richards, Memoir 13; Jane L. Silverman, Kaahumanu, Molder of Change (Honolulu: Friends of the Judiciary History Center of Hawai'i 1987) 30. 31 Richards, Memoir 13; Valerio Valeri, Kingship and Sacrifice: Ritual and Society in Ancient Hawaii (Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1985) 149. 32 Kamakau, Ruling Chiefs 208, 260; Kamakau, Ka Poe Kahiko 10. 33 Kamakau, Ruling Chiefs 221. 34 Kamakau, Ruling Chiefs 260. 35 Kamakau, Ruling Chiefs 176, 190. 36 Barrere, Kamehameha in Kona 3—4. 37 W. D. Alexander, "Overthrow of the Ancient Tabu System in the Hawaiian Islands," HHS Report 1916 (Kraus Reprint, Millwood 1978) 39. 38 Lorrin Andrews, A Dictionary of the Hawaiian Language (Rutland, Vt.: Charles E. Tuttle, 1974) 314; Kamakau, Ka Poe Kahiko 35; Pukui and Elbert, Hawaiian Dictionary 167. 39 Kamakau, Ruling Chiefs 222—23. 40 Linnekin, Sacred Queens 70. 41 Kamakau, Ruling Chiefs 222-23. 42 "History of Hawaii," Hawaiian Spectator (1839) 2: 335. 43 Kamakau, Ruling Chiefs 215; Kamakau, Ka Poe Kahiko 41. 44 Kamakau, Ruling Chiefs 187, 188, 209. 45 Kamakau, Ruling Chiefs 220. 46 Alexander, "Overthrow" 41. 47 Silverman, Kaahumanu 64.

24 THE HAWAIIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY

48 Kamakau, Ruling Chiefs 224. 49 Kuykendall, Hawaiian Kingdom 68. 50 Linnekin, Sacred Queens 59. 51 Kuykendall, The Hawaiian Kingdom 68; Barrere, Kamehameha in Kona 34; Kamakau, Ruling Chiefs 225; Charles S. Stewart, Journal of a Residence in the Sandwich Islands (Honolulu: U of Hawai'i P, 1970) 35-36; Alexander, "Overthrow" 42. 52 Kuykendall, The Hawaiian Kingdom 69. 53 Richards, Memoir 18. 54 Kamakau, Ruling Chiefs 250-52. 55 Kamakau, Ruling Chiefs 261—62. 56 Kamakau, Ruling Chiefs 261-62; Hiram Bingham, A Residence of Twenty-One Years in the Sandwich Islands (Rutland, Vt: Charles E. Tuttle, 1981) 183. 57 Richards, Memoir 20. 58 Richards, Memoir 30-33. 59 Marjorie Sinclair, 'The Sacred Wife of Kamehameha I Keopuolani," HJH 5 (1971): 20. 60 Richards, Memoir 36. 61 Stewart, Residence 208; Klieger, "Mokuula" 35.

Reference: file:///C:/Users/amy/Documents/Keopuolani%20copypdf.pdf

https://evols.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/handle/10524/569/JL32007.pdf?sequence=2

Keopuolani, Sacred Wife, Queen Mother, 1778-1823

KEOPUOLANI, DAUGHTER OF KINGS, wife of a king, and mother of two kings, was the last direct descendant of the ancient kings of Hawai'i and Maui and the last of the female ali'i (chief) whose mana was equal to that of the gods. From May 1819 to March 1820 she was the central figure in the kingdom's history. Her husband, Kamehameha, had already united the islands under his rule. On May 8 or 14, 1819, he died in Kailua, Kona. It was during the mourning period that the ancient kapu system collapsed, and Keopuolani was instrumental in this dramatic change. Six months later, when her first-born son, Liholiho, heir to the kingdom, was challenged by Kekuaokalani, his cousin, Keopuolani, the only female ali'i kapu (sacred chief), confronted the challenger. She tried to negotiate with him so as to prevent a battle that could end with her son's losing the kingdom. The battle at Kuamo'o was fought, Kekuaokalani was killed, and Kamehameha IPs kingdom was saved. Three months later, the first of the American Protestant missionaries arrived in Kailua, Kona, with a new religion and a system of education. Keopuolani was the first ali'i to welcome them and allowed them to remain in the kingdom. Information about her personal life is meager and dates are few. There is no known image of her, although there was a sketch done of her by the Reverend William Ellis, a member of the London Missionary Society, who lived in the Hawaiian kingdom for two years,

Esther T. Mookini translates for the Judiciary History Center of Hawai'i, Honolulu.

The Hawaiian Journal ofHistory, vol. 32 (1998)

2 THE HAWAIIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY

1822-1823. However, that sketch was lost during the time his Journal of William Ellis was being published in London, sometime between 1825 and 1828. In his Journal there are sketches of people and landscapes as British missionaries were trained in sketching (David Forbes, personal communication, 1997). American Protestant missionaries who came to Hawai'i in 1820 did much writing: letters, papers, accounts, diaries, and journals. They were consistent about writing regularly to their office in Boston and to their friends and families regarding their work. Their sketches were few, mainly of their houses and surroundings. Among these missionaries, some of the wives may have had painting lessons, but the men generally had not even received rudimentary drawing lessons.1 In April 1823 the second company of American missionaries arrived, bringing the Reverend William Richards and the Reverend Charles Stewart. Keopuolani immediately asked that these missionaries accompany her to Lahaina, Maui, where she lived her last five months under their religious guidance, along with Taua, a Christian Tahitian. Richards and Stewart wrote of her conversion to Christianity with deep feeling, that she had indeed shown her desire to be baptized. The two men drew a picture of Keopuolani in words. Samuel M. Kamakau pictured her in Hawaiian words in his articles published in the Hawaiian newspapers, Ka Nupepa Kuokoa, 1866—1869, and Ke Au Okoa, 1869-1870, which were translated by Mary Kawena Pukui and published under the title Ruling Chiefs of Hawaii. William Richards's Memoir of Keopuolani, Late Queen of the Sandwich Islands, published in 1825 in Boston and London and later in France, was to inform the Western nations of the conversion of Keopuolani and that the mission to the Sandwich Islands was on its way to success because of her influence among her people. This information was crucial to Americans and Europeans who had already penetrated the Pacific for political and commercial gain. It was of great significance for them to know that the chiefs in the kingdom were being educated and Christianized. Westerners who came to Hawai'i from 1778 to 1820 were traders, whalers, and those on scientific expeditions sent out by foreign nations. There were artists on board, but they were more interested in sketching landscapes and painting portraits of chiefs, among whom

KEOPUOLANi: SACRED WIFE, QUEEN MOTHER 3

were Ka'ahumanu, Kamehameha, Boki, and Ke'eaumoku but not Keopuolani. Perhaps the Westerners did not notice her because she was not in the forefront of politics and commerce like her sisterqueen, Ka'ahumanu. Perhaps it was because of her kapu moe (prostrating tabu), which prevented people from looking upon her. The written picture of Keopuolani is that of a dutiful child, responsible wife and mother, and a chief who abided by and respected the ancient traditions. She was obedient to the chiefs, her husband, and all people. Her sister-queens spoke of her with admiration due to her mild disposition. She was amiable and affectionate and known to be gentle and considerate, tender and loving, kind and generous. She was strict in the observance of the kapu (tabu) but mild in her treatment of those who had broken it, and they often fled to her for protection. She was said by many of the chiefs never to have been the means of putting any person to death. There is another picture of Keopuolani and that is of her at play. When the Thaddeus arrived in Kailua bay, Kona, the Reverend Hiram Bingham wrote of a great number of people—men, women, and children, from the highest to the lowest rank, including the king and his mother—amusing themselves in the water. They were at Kamakahonu, where a spring, Ki'ope,

FIG. 1. Funeral procession of Keopuolani. Watercolor sketch by William Ellis. (Hawaiian Mission Children's Society)

4 THE HAWAIIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY

mixes with sea water, a favorite gathering place for swimmers and surfers.2 Three years later, in 1823, she moved to Lahaina, taking her daughter, Nahi'ena'ena, along with missionaries Richards and Stewart and their families, as she was seriously contemplating becoming a Christian. It may have been her relatively unstable physical health throughout her adult life that led her to believe in Christ. In 1806, at Waikiki, she was so ill that Kamehameha thought she was going to die. He offered human sacrifices to restore her health, but before all the victims were sacrificed, she recovered. In the spring of 1823 she was again in poor health. She became more attentive to the Gospel as she was resting. It was Taua who became the teacher she relied on as perhaps they were able to converse with each other in the Polynesian language. Three months later, in the last week of August, she fell very ill. Two weeks later, she was dead. The funeral ceremonies, after the Christian manner, were held two days later with chiefs, missionaries, and foreigners surrounding the corpse. All were respectably dressed in the European style. During the whole time, the most perfect order was preserved.3

KEOPUOLANI'S GENEALOGY

Keopuolani (the gathering of the clouds of heaven), was the highest ranking chief of the ruling family in the kingdom during her lifetime. She was ali'i kapu of ni'aupi'o (high-born) rank, which she inherited from her mother, Keku'iapoiwa Liliha and her father Kiwala'o. Born in 1778 or 1780 at Pahoehoe, Pihana, Wailuku, Maui,4 her name, given at birth, was Kalanikauikaalaneo (the heavens hanging cloudless). She may have been named for her ancestor, Kakaalaneo, who, with his brother, Kakae, ruled Maui and Lana'i from their court in Lele, the ancient name of Lahaina. It was Kakaalaneo who planted the breadfruit trees in Lahaina for which the place became so famous as to be called Malu Ulu o Lele (breadfruit groves of Lele) .5 Kakaalaneo's time as ali'i of Maui was after regular voyages between Hawai'i and the southern islands ceased, and he was named in a chant as the stranger forefather from Kahiki.6 His direct ancestor was Mooinanea, a mythical mo'o 'aumakua (lizard guardian spirit). She was called by

KEOPUOLANI: SACRED WIFE, QUEEN MOTHER 5

other names such as Makuahanaukama (mother of many children) as she was said to have had eleven or twelve children by Kamehameha, but only three survived. She was also called Wahinepio (captive woman), as she was "captured" on Moloka'i by Kamehameha, but she was most commonly known as Keopuolani, a name given to her when she was fifteen or seventeen years old.7 Her ancestors on her mother's side were ruling chiefs of Maui as far back as Kakaalaneo. She was called queen of Maui.8 Her mother

Mo'oinanea

Mythical

Kakalalaneo Kakae

Kahekili I

Kings of Wailuku

Kalamakua = Kelea Kawao Kaohele

Laielohelohe = Pi'ilani Kings of Maui 16th century

Umi-a-Liloa — Pi'ikea Kala'aiheana = Kamalama Lono-a-Pi'ilani Kiha-a-pi'ilani Kihawahine Kuihewakanaloahano = Nihoa Kamalama Kamalawalu (Waiokama)King s of Hawaii

Keawepaikanaka = Maluna Kahakumaka Kualu

Konokaimehelai = Kihalaninui

Hilia = Kamalau I Waiau = Kahiko

Kapao = Haalou

Kauhi-a-Kama 17th Century I Kalani-Kaumakaowakea

Lonohonuakini I Kaulahea

Keku'iapoiwanui 2 Kekaulike 18th Century

Keku'iapoiwa II = Keoua = Kalola = Kamehamehanui Kahekili II Kauhiaimokuakama Kamae — 'Aikanaka

Keohokalole = Kapa'akea Kamehameha I = Keopuolani

Kalanikupule Kalanikauiokikilo-kalani-akua Kalani'opu'u

Keku'iapoiwa Q Kiwala'o Liliha I

19th century

Liholiho Kauikeaouli Nahi'ena'ena

Kalakaua Lili'uokalani, etc.

Kings of the Hawaiian Islands

mo'o Q pi'o or ni'aupi'o

FIG. 2. The genealogy of Keopuolani. From P. C. Klieger, ed., "Mokuula, History and Archaeological Excavations" (Bishop Museum, 1975), p. 2.

6 THE HAWAIIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY

was named after her great-grandmother, Keku'iapoiwanui, wife of Kekaulike, the paramount chief of Maui. The children of Keku'iapoiwanui and Kekaulike were Kalola Pupukaohonokawailani, ali'i kapu of Maui and Hawai'i, and her brother, Kahekili, ruling chief of Maui and O'ahu. Kalola lived with two brothers, Kalani'opu'u and Keoua, both Hawai'i island ni'aupi'o chiefs. From Kalani'opu'u, the older brother, she had a son, Kalanikauikeaouli Kiwala'o, more often called Kiwala'o. From Keoua, the younger brother, she had a daughter, Keku'iapoiwa Liliha. The children, Kiwala'o and Keku'iapoiwa, had the same mother, different fathers, offspring of a naha union. These two lived together, and Keopuolani was born, the offspring also of a naha union. She was their only child who inherited her ni'aupi'o rank from both parents. A ni'aupi'o chief was of very high rank, and this rank was passed from a ni'aupi'o chief to his or her children. They could never lose that rank. Chiefs of ni'aupi'o and pi'o ranks from naha unions were considered the most sacred of all high chiefs, and these unions were carried out to assure succession to royal power and to obtain the intensified mana important to community and family life.9 Her ancestors on her father's side were of the blood of chiefs who had ruled the island of Hawai'i for as many generations back as the genealogies extend. Her father was Kiwala'o, his father was Kalani'opu'u, and his father was Kalaninuiiamamao, the first-born of the ruling chiefs over all Hawai'i island. Keopuolani's and her ancestors' genealogies were called Kumuuli and Kumulipo, which are found in the song of the kapu chiefs of O'ahu—Kualii, Peleioholani, and Kahahana. The genealogy of Kumuuli, which was much praised by the ancient Hawaiian chiefs and quoted in the famous chant of Kualii, the warrior king of O'ahu, was recited in honor of Keopuolani, who was the kapu descendant of the Maui line of kings. The O'ahu chiefs have no direct descendants in this world; their genealogies trace back through the ancestors of Keopuolani, who bore Kamehameha II and Kamehameha III.10 There were nine traditions that emphasized chiefly rank: one was having a family genealogy tracing back to the gods through Ulu or Nanaulu. Keopuolani's genealogy traced back to Ulu, who descended from Hulihonua and Keakahulilani, the first man and woman created by the gods. Another tradition was that a name chant be composed at birth or given in afterlife, glorifying the family history.11

KEOPUOLANi: SACRED WIFE, QUEEN MOTHER 7

Kiwala'o was present at the birth of Keopuolani as he and his wife were visiting her brother, Kahekili, who, at that time, was the king of Maui, Lana'i, Moloka'i, and O'ahu. Soon after the birth of his daughter, Kiwala'o returned to Hawai'i to become ruling chief over that island. The child remained on Maui as she was hdnai (brought up) in Wailuku, Olowalu, and Hamakua by her maternal grandmother, Kalola. It was not customary for the chiefs to bring up their own children.12

KEOPUOLANI'S CHILDHOOD

Keopuolani was reared under strict kapu because she was sacred; her kapus were equal to those of the gods. At the time she was being nursed by her wet nurse, neither chief nor commoner dared approach or touch her; anyone who disobeyed this kapu was burned to death. She possessed kapu moe, which meant that those who were in her presence had to prostrate themselves, face down, for it was forbidden to look at her. At certain seasons, no person was allowed to see her. In her childhood and early adulthood, she never walked out during daylight hours. The sun was not permitted to shine upon her. As a result, extraordinary precautions had to be made before she could move about, and this she did only after the sun was so low as not to shine on her. Should her shadow fall on anyone, that would mean his immediate death. Should it fall on the ground, that ground would be kapu, and so she chose to be among people at night. She did this for the benefit of the people and was known to be gentle and considerate. The ordinary people did not ever see the chiefs because of their kapu, and those chiefs of the highest rank were named for a god or by lani (heaven), where the gods lived.13 Keopuolani's grandfather, Kalani'opu'u, was an old man and was not expected to live many years longer. He called a council of chiefs in Waipio valley, and there he designated his son, Kiwala'o, his successor, based on his ni'aupi'o rank, which came from his mother, Kalola.14 Kalani'opu'u died about four years after Keopuolani's birth. His bones were taken by his sons, Kiwala'o and Keoua, who were accompanied by their uncle Keawemauhili, the cousin Kamehameha, chiefs of Kona, and other chiefs and were deposited in Hale o Keawe at Honaunau, Kona. There the distribution of land was made, with

8 THE HAWAIIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY

Keawemauhili having his way to the disadvantage of Kiwala'o and Keoua, as well as Kamehameha and the Kona chiefs. But when battle lines were drawn, it was Kiwala'o, Keoua, and Keawemauhili against Kamehameha and the Kona chiefs. The actions of Kiwala'o and his brother were illogical. The only rational explanation of their course appears to be that a plan had been prearranged between the uncle and the two brothers to provoke a quarrel with Kamehameha and the Kona chiefs, defeat them in battle, and strip them of their possessions. In the battle of Moku'ohai in 1782 Kamehameha and the Kona chiefs were victorious.15 When Kiwala'o was killed, Kalola, her daughters Keku'iapoiwa and Kalaniakua, and her granddaughter, fouryear-old Keopuolani, fled to Maui, for they had taken refuge with her brother, Kahekili, and his son, Kalanikupule.16 The victory at the battle of Moku'ohai was the start of Kamehameha's rise to power. The island was divided into three kingdoms: Kamehameha held Kona, Kohala, and the northern part of Hamakua; Keoua held Ka'u, and part of Puna; Keawemauhili held Hilo and took parts of Hamakua and Puna. For nearly four years the three kingdoms on Hawai'i island were at peace. The first recorded foreigner in Hawaiian waters was Captain James Cook, who came in January 1778, the year Keopuolani is said to have been born. He was killed at Kealakekua in January 1779. After his ships left, no foreign ships are known to have visited Hawai'i until 1786, when two British and two French naval vessels came, opening the Islands to European nations, which saw them as a place for colonization or for the promotion of commerce.17 The American trading ships Ekanora and Fair American came into Hawaiian waters in 1790. Kamehameha took possession of the Fair American and at the same time acquired the services of American sailors John Young and Isaac Davis. Armed with a Western ship, guns, and two Western advisors, Kamehameha decided to attack Maui as Kahekili's forces would be no match for his new weapons. Twelve-year-old Keopuolani, her mother, and her aunt were with Kahekili when the battle of Kepaniwai (the damming of the waters) was fought in Tao Valley, Wailuku. Kamehameha' s men destroyed the Maui forces, whose bodies dammed up the water of the Wailuku (water of destruction), hence perhaps the name of the river.18

KEOPUOLANK SACRED WIFE, QUEEN MOTHER 9

KEOPUOLANI'S "CAPTURE" BY KAMEHAMEHA

Kalanikupule, Kahekili's son, and some of his chiefs escaped to O'ahu. Keopuolani, her mother, Keku'iapoiwa, and her aunt, Kalaniakua, fled over the pass in 'Iao valley to Olowalu, where they joined Kalola and all escaped to Kalama'ula, Moloka'i. They could not continue on to O'ahu to be under the protection of Kalola's brother, Kahekili, because Kalola was too ill to travel any further. Kamehameha could have gone after Kahekili on O'ahu, but he felt it would be sound policy to make peace with Kalola and try to get her two daughters and granddaughter in his possession. He sent a messenger to Kalola asking her not to go on to O'ahu but to go with him back to Hawai'i island, where she and her daughters and her granddaughter would be provided for as became their high rank. Kamehameha took a great company to Moloka'i, among them Kame'eiamoku and Kamanawa, twin brothers of Kalola. When they landed at Kaunakakai, they were told that Kalola was very sick and not expected to live. He went at once to her and asked her: "Since you are so ill and perhaps about to die, will you permit me to take my royal daughter and my sisters to Hawai'i to rule as chiefs?" Kamehameha called Keopuolani his daughter because Kamehameha had grown up with Kalola's son, Kiwala'o, and the two were as brothers.19 Ii stated that Kamehameha and Kiwala'o shared Keku'iapoiwa, and in that way he saw himself as Keopuolani's father.20 Kamehameha referred to Keopuolani as his kaikamahine (daughter or niece), and when their children, Liholiho, Kauikeaouli, and Nahi'ena'ena were born, he called them his grandchildren in respect to their lineage as chiefs.21 Agreeing to Kamehameha's offer, Kalola was doing what Hawaiian women had always done, that is, controlling not only their own reproductive potential but also that of their daughters and granddaughters because children were their most important product.22 She knew, too, that Kamehameha, an aspiring ruler, needed to produce children by the highest ranking woman, and that woman was her granddaughter, Keopuolani. When Kalola died, Kamehameha and all the chiefs wailed and chanted dirges; the chiefs tattooed themselves and knocked out their teeth.23 When the mourning period was over and Kalola's bones were deposited in a secret cave in Kaloko, Kekaha, Hawai'i, Kamehameha

1O THE HAWAIIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY

took charge of her two daughters and her granddaughter, not only as a legacy from the mother but as a seal of reconciliation between himself and the representatives of Kiwala'o, the Keawe dynasty.24 This "capture" of the women by Kamehameha, a conquering chief taking the widow and female relatives of his defeated rival, was politically important. Most noteworthy was the manner in which he "captured" them, asking a high-ranking chiefess for the women and going to great lengths to pay respect to her; not using force and addressing only Kalola, the female head of the matriline; and following the rules of conduct during the mourning period.25 Kamehameha fully recognized that Keopuolani was, among all the chiefesses, the only heir to the nine traditions that emphasized her rank. One such tradition was regarding genealogy, another was a chant at the birth or death of a chief glorifying the family history, and another was the power of the kapu, which certain chiefesses of Maui (Kalola, her two daughters, and her granddaughter) of incredible sanctity possessed and before whom all had to remove their garments.26 Kamehameha knew too that she was descended directly from Kihawahine, the powerful Maui mo'o 'aumakua, which he needed to have in his assemblage of gods if he was to succeed in conquering the Islands. He believed, as others did, that the kingdom that cared for (malama) Kihawahine prospered. He already possessed the war god Kuka'ilimoku (land snatcher) and now by his "capturing" Keopuolani, he acquired Kihawahine (land holder). He knew too that his children from Keopuolani would further tie the senior line of Hawai'i tightly with that of the prestigious Piilani lineage of Maui as it had before when Kalola of Maui married Kalani'opu'u, Hawai'i chief, and before them when Piikea, Maui chiefess, married Umialiloa, Hawai'i chief. His children would inherit the superior ni'aupi'o rank and be associated with Kihawahine through their mother, Keopuolani. In obtaining these women, Kamehameha also adopted Kihawahine.27 Kamehameha's wives came mainly from Maui since the chiefs of Hawai'i and Maui were closely related.28 His first wife was Kalolaakumukoa, daughter of Moloka'i chief Kumukoa. He had her before the battle of Moku'ohai, before he gained prominence. They had no children. He was also married to Kanekapolei, who bore him his first

KEOPUOLANi: SACRED WIFE, QUEEN MOTHER 11

child, a son, Ka'oleioku, but he did not appear in line to succeed his father. Peleuli, an aunt of Keopuolani, became another of his wives. Ka'ahumanu, first-born of Ke'eaumoku, the most beautiful woman in Hawai'i in those days, became his wife in 1785. She was treated with utmost respect but not given ceremonial kapu, which would have been hers if she were ali'i kapu. In 1789 Kamehameha deserted Ka'ahumanu for a while and lived entirely with Kaheiheimalie, Ka'ahumanu's sister, who was already married to Kamehameha's brother and who matured into a beautiful woman after bearing a child, much to the grief of Ka'ahumanu, who had been his favorite wife. There was no woman of his household whom Kamehameha loved as much as he did Kaheiheimalie. Kahakuha'akoi, or Wahinepio, sister of Kalanimoku and Boki, was Kamehameha's third favorite wife, after Ka'ahumanu and Kaheiheimalie. Another of Ka'ahumanu's sisters, Piia or Kekuaipiia, sometimes called Namahana, was also his wife. In his old age he brought two young chiefesses, Kekauluohi and Manono, into his household. Eight of these wives traced their descent to Kekaulike, Maui chief.29 When Keopuolani was "captured" by Kamehameha she was about ten or twelve years old. She, her mother, and her aunt were taken to live in Keauhou, North Kona. Keopuolani was celebrated for her beauty, and because she was "captured," she was then called by the name Wahinepio (captive woman). Vancouver wrote in his Voyages a description of a hula that he attended near Kealakekua Bay: 'The piece was in honour of a captive princess whose name was Kalanikauikaalaneo" (Keopuolani's name in her childhood). This was a farewell hula in honor of Vancouver danced by the a/i'iwomen. The hula was the story of the captured Maui child, Keopuolani, who possessed the most powerful kapu. As the dancers told her story, even at the mere mention of her name, although she was on the other side of the island, the audience—chiefs and commoners alike—had to remove all ornaments and clothing above the waist. Ka'ahumanu and Kamehameha would have had to do the same had they been present. 30 In 1795 Kamehameha attacked O'ahu at the battle of Nu'uanu. Keopuolani, who was about seventeen or eighteen years of age, and her mother accompanied Kamehameha when he fought and was vie

12 THE HAWAIIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY

torious over Kalanikupule. Richards said: "Her person was seen as so sacred that her presence did much to awe the enemy." Valeri stated that "an ali'i having the kapu moe can always end a battle by becoming visible and thus forcing everyone to throw down his weapons and fall prostrate."31 It was here that an O'ahu chief gave her the name Keopuolani, by which she was known until her death. It was also perhaps at this time that she was formally hodo (united) with Kamehameha in Waiklki. She was not his constant companion, for he slept with her only from time to time in order to perpetuate the high chiefly blood of the kingdom, which his children from her would inherit. 32 In 1797 she gave birth to a son, Kalani Kua Liholiho. Kamehameha wanted Keopuolani to go to O'ahu, to Kukaniloko, a famous birthing site and heiau (place of worship). Kukaniloko was another of the nine traditions that emphasized rank. Keopuolani was too ill to travel, however, and so gave birth to their first-born child in Hilo. Liholiho was taken by Ka'ahumanu, his hdnai mother, to be brought up in the presence of his father, the ruling chief. Keku'iapoiwa, Keopuolani's mother, and Kalaniakua, her aunt, were also constantly taking part in the child's upbringing.33 On March 17, 1814, Kauikeaouli, her second son, was born in Keauhou, North Kona. She named him after her father, Kalanikauikeaouli Kiwala'o. The baby was adopted (hdnai) by chief Kaikio'ewa. The following year, her daughter, Nahi'ena'ena, was born. Keopuolani loved her children and wept when her two sons were taken away from her, to be brought up by other chiefs. When Nahi'ena'ena was born, Keopuolani would not give her up.34 While Kamehameha was still alive he allowed Keopuolani to have other husbands after she gave birth to his children, a practice common among ali'i women, except Ka'ahumanu. Kalanimoku and Hoapili were her other husbands. Kalanimoku held the highest position in the kingdom as treasurer, regent, chief counselor, and supreme war leader. He had power over the laws of life and death and over Kamehameha's daughters, sisters, cousins, and other chiefesses, who were free to him as wives. Hoapili was a loyal counselor related to the Maui chiefs. His father was Kame'eiamoku, one of Kamehameha's most trusted generals. It was a great honor for Hoapili to guard the ruling kapu family of Hawai'i.35

KEOPUOLANI: SACRED WIFE, QUEEN MOTHER 13

KEOPUOLANI AND THE END OF THE KAPU SYSTEM